Deadly High Altitude Pulmonary Disorders: Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS); High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE): A Clinical Review-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PULMONARY & RESPIRATORY SCIENCES

Abstract

Mountain Sickness, also called High Altitude

Sickness, is specifically a triad of different disorders, in order of

increasing seriousness: Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS); High Altitude

Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). These

three disorders, with relatively unimportant small variations seen in

some Pulmonology Textbooks, because these are so serious, they are all

potentially deadly pulmonary disorders and we will discuss these three

major, deadly disorders. Each one, starting with AMS, can progress

rapidly to HAPE and then HACE. The two authors of this article have over

half a century of high altitude mountaineering experience. They have

also had and still do have, for the last twenty years, an NGO,

Non-Profit Medical Organization (Wilderness Physicians

www.wildernessphysicians.org) that specifically deals with outdoor

medical issues, wilderness search and rescue, providing hospital level

care in the wilderness and also disaster medicine. Since spring is

rapidly approaching and many “weekend backpackers” will start going into

the mountains, we present this paper with the truths and fallacies of

this triad of disorders to refresh the memories of physicians who treat

these disorders, either in the field or in the hospital.

Abbreviations: AMS: Acute Mountain Sickness; HAPE: High Altitude Pulmonary Edema; HACE: High Altitude Cerebral Edema; DVT: Deep Vein Thrombosis; PE: Pulmonary Embolism

The mildest form of altitude sickness is Acute

Mountain Sickness (AMS). Where and how does acute mountain sickness

happen? Most people in “relatively” good physical condition, remain

feeling well up to altitudes of about 2500meters (8200 feet), the

equivalent barometric pressure to which most modern airplane cabins are

normally pressurized. However, even at around 1500meters (4920 feet)

above sea level, patients may notice more breathlessness than normal

during exercise and night vision may become impaired due to lack of

oxygen to the ocular apparatus. Above 2500meters (8200 feet), the

symptoms of altitude sickness usually become more noticeable.

Acute Mountain Sickness is sometimes colloquially

referred to as altitude sickness or mountain sickness; in South America

it is called Soroche, in China it is called Jíxìng Gāoyuán Bìng and in Nepal it is called Tīvra Pahāḍa Rōga.

The most prominent symptom of AMS is usually a severe

headache. Most people also experience nausea, vomiting, dehydration,

lethargy, dizziness and poor sleep patterns. Symptoms are very similar

to a severe, alcohol-induced hangover.

Anyone who travels to altitudes over 2,500meters

(8,200 ft.) is at risk for AMS. Normally it does not become noticeable

until the patient has been at that altitude for a few hours. Part of the

mystery of acute mountain sickness is that it is difficult to predict

who will be affected. There are many stories of fit and healthy people

being badly limited by symptoms of acute mountain sickness, while older

companions have felt fine.

There are a number of factors that are linked to a

higher risk of developing the condition. The higher altitude you achieve

and the faster your rate of ascent, the more likely you are to get

acute mountain sickness. If you have a previous history of suffering

from acute mountain sickness, then you are probably more

likely to get it again. Older people tend to get less AMS – but this

could be because they have more common sense and ascend

less quickly. Physical fitness is a suspected key factor, obviously

because the patient is in better condition. Smokers are at a

much higher risk of AMS due to already having decreased lung

function and lung elasticity, combining that with low oxygen

concentration at higher altitude increases the probability of

AMS, HAPE and HACE [1].

There is much less oxygen high in the mountains so it is

reasonable to accept the fact that travelling to high altitude will

cause people to feel sick. The problem is, how this shortage of

oxygen actually leads to altitude sickness is not fully understood.

Some scientists believe that it is due to swelling of the brain but

the evidence for this hypothesis is not conclusive. The theory

is that in susceptible individuals, swelling could cause a small

increase of the pressure inside the skull and lead to symptoms of acute mountain sickness. The swelling may be due to increased

blood flow to the brain or any increased permeability [2] of blood

vessels in the brain caused by a decrease in the pO2. Altitude

sickness has three forms. Mild altitude sickness is called acute

mountain sickness (AMS) and is quite similar to a hangover - it

causes headache, nausea and fatigue. This is very common: some

people are only slightly affected, others feel very sick. However,

if a patient has AMS, this should be taken as a warning sign that

this patient is at risk of developing the serious forms of altitude

sickness: HAPE and HACE. Both HAPE and HACE can develop

rapidly and be fatal within hours.

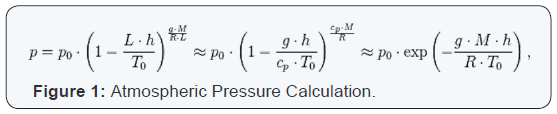

Atmospheric Pressure (also called Barometric Pressure) at

sea level is 14.7 psi (101.3 kPa). For calculating any atmospheric

pressure within the troposphere (from the surface of the earth

up to an altitude of about 12 miles or 20 km.) use this simple

formula [3] Figure 1.

Where the Constant Parameters are as Described Below

This ability to calculate the atmospheric pressure can quite

accurately help with treatment of the patient, however we will

repeat this several times, the single most important treatment is

to evacuate the patient down the mountain.

It is better to prevent acute mountain sickness than to try

and treat it! The patient needs to follow the “Golden Rule

of Mountaineering” and ascend slowly, which will give their

body time to acclimatize as they ascend. They will be less

likely to develop AMS. If a back packer has been climbing for

any amount of time, they will see the most experienced (and

smartest) mountaineers climbing at a SLOW, steady pace. This

is not because they are old and decrepit, this is because they are

smart and are slowly acclimatizing to the increase in altitude.

However, if a mountaineer needs to go up more quickly, they

could consider taking a drug called acetazolamide (also known

as Diamox). Acetazolamide is a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor

that is used for the medical treatment of glaucoma, epileptic

seizures, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, altitude sickness,

cystinuria (a rare condition in which stones made from an amino

acid called cysteine form in the kidney, ureter, and bladder),

periodic paralysis, central sleep apnea and dural ectasia (a

widening of the dural sac surrounding the spinal cord).There

is now good evidence that acetazolamide reduces symptoms of

AMS in trekkers and mountaineers, although it may have some

unusual side-effects such as causing the extremities to tingle or

food, especially fluids, taste strange.

As with any of the three forms of altitude sickness, if the

patient has acute mountain sickness, the best treatment is

descent. Painkillers may ease the headache, but they will not

treat the condition. Acetaminophen (Paracetamol) is the safest,

avoid these pain killers if they have codeine in them, as there are

no definitive studies on the effect of codeine on AMS. The patient

may be extremely thirsty, however increasing fluid intake should

be done with caution, as an increased intravascular volume can

exacerbate HAPE and HACE. If possible, a 22 Gauge (25 mm.)

I.V. Catheter (Venflon®) should be securely placed and either

flushed with heparin and capped off or if a long transport down

the mountain is expected in a Gamow Bag or on a stretcher, you can give 0.9% Normal Saline at a TKO (To Keep Open) rate or D5W,

also at a TKO rate. Avoid colloids because again, the effects of

colloids on the brain in HACE have not been extensively studied.

Acetazolamide may be helpful, especially if the patient needs to

stay at the same altitude. DO NOT however delay descending

with the patient in order to place an I.V. Catheter. The priority

is to get the patient to descend as rapidly as possible and the

patient should be strongly encouraged to descend, regardless

of the reason they need to stay up high, as they may rapidly

develop HAPE or HACE and die. Resting for a day or two at a

lower altitude might give their body time to acclimate and then

they can attempt to increase their altitude again, but even slower

than before. It is not clearly understood why, but once a patient

has had AMS, they are more susceptible to reoccurrences. It is

essential that the patient should NEVER go up higher, instead

of lower, if they have AMS as they will exacerbate the symptoms

and risk rapidly progressing to HAPE or HACE. This triad always

has to be thought of concomitantly during the treatment of

anyone with the initial symptoms of AMS.

- If you feel unwell, you have altitude sickness until proven otherwise

- Do not ascend further if you have any symptoms of altitude sickness

- If you are getting worse then descend immediately

- Do not descend alone, you don’t know what may happen

- Don’t die of altitude sickness.

Every year, people die of altitude sickness. All of these deaths

are preventable. If the person is travelling above 2500 meters

(8200 feet), this information could save their life.

Two things are certain to make altitude sickness very likely

- ascending faster than 500 meters = 1,965 feet) per day and

exercising vigorously (ie: backpacking). Physically fit individuals

are not protected – even Olympic athletes get altitude sickness.

Altitude sickness happens because there is less oxygen in the air

that you are breathing at high altitudes.

Gain altitude slowly, take it easy and give your body time

to get used to the altitude. The body has an amazing ability to

acclimatize to altitude, but it needs time. For instance, it takes

about a week to adapt to an altitude of 5000 meters (16,404 feet),

two weeks is better. When these two authors hiked up to “Base

Camp Everest South”(28°0′26″N 86°51′34″E) (5364 meters

= 17,598 feet) they took two weeks of slow backpacking from

Kathmandu to Base Camp Everest South. To save time and energy before beginning the trek to Everest Base Camp, it is possible to

take a plane to Lukla, but not recommended by these doctors due

to the sudden increase in altitude. Nevertheless, the two authors

of this article trekked from Kathmandu 1,400 meters (4,620

ft.) to Lukla at 2,843 meters (9,383 ft.) and rested overnight.

From Lukla, they trekked upwards to the City of Namche Bazaar,

which is often called the Sherpa Capital of Nepal because this

is where most Everest Expeditions hire their Sherpas and get

supplies. Namche Bazaar is situated at 3,440 meters (11,286 ft),

following the Valley of the Dudh Kosi River. It took about two

days of easy hiking to reach this village, which is a central hub

of the area and full of wonderful local people. Typically at this

point, climbers allow another day of rest for acclimatization,

which the two authors did. When the locals found out we were

doctors, they came to us with every ailment imaginable – but

it was a wonderful experience and these terribly poor people

paid us in some of the most wonderful food we have ever eaten

and their magnificent company. The children were an absolute

joy and they could not believe that a father and daughter doctor

team actually existed. I don’t think we cooked a single meal in

any of the towns we stopped in due to the wonderful generosity

of the Nepalese People. We then trekked another two days to Dingboche at 4,260 meters (13,976 ft.) before resting for

another day for further acclimatization. Another two days took

us to Everest Base CampSouth (5364 meters = 17,598 feet)

via Gorakshep, the flat field below Kala Patthar, 5,545 meters

(18,192 ft) and Mt. Pumori. The reason we relate our personal

trek into veryhigh altitudes is because neither one of us suffered

from any kind of AMS, one of us is past 40 and the other is in her

20’s! If you just fly in, you miss the beauty of the countryside, the

incredible people of Nepal, their hospitality and their incredible

love of life and nature and you are at a very high risk of AMS!!

HAPE stands for High Altitude Pulmonary Edema and this

termsimply means “excess fluid accumulation in the lungs”.

Everyone who travels to high altitude should know about this

triad (AMS, HAPE, HACE) and the fact that death can result

rapidly from these disorders, do not ignore the symptoms!

HAPE is a dangerous build-up of fluid in the lungs that

prevents the alveoli from opening up and filling with fresh air

with each breath. When this happens, the patient becomes

progressively more and more short of oxygen, which in turn

worsens the build-up of fluid in the lungs. In this way, HAPE can

be fatal within hours.

HAPE usually develops after 2 or 3 days at altitudes above

2500 meters (8,202 feet). Typically the sufferer will be more

breathless compared to those around them, especially on

exertion. Most patients will have symptoms of acute mountain sickness. Often, they will have a cough and this may produce a

white or pink frothy sputum. The breathlessness will progress

and soon they will be breathless even at rest. Heart rate may

exhibit tachypnea, the lips may be cyanotic and the body

temperature may be elevated. It is easy to confuse symptoms

of HAPE with a chest infection, but at altitude HAPE must

be suspected as your primary differential and the affected

individual must be evacuated to a lower altitude immediately,

preferably accompanied by the highest ranking medical person

by education(in order of preference: physician, nurse or

paramedic) on the mountain.

Unfortunately, it is currently impossible to predict who will

get HAPE. People who have had HAPE before are much more

likely to get it again. Therefore, there must be some factor that

puts certain individuals at high risk of the condition. However,

just like acute mountain sickness, there are some known risk

factors. A fast rate of ascent and the altitude attained will make

HAPE more likely. Vigorous exercise is also thought to make

HAPE more likely and anecdotal evidence suggests that people

with chest infections, symptoms of a common cold before ascent

or smokers [1] may be at higher risk. One very good axiom to

follow is to “climb high, sleep low” (Obrowski, M.H. – Denali –

1986 – unpublished). What this basically means that if you are

attempting to climb a high mountain in stages (such as Denali,

formerly known as Mt .McKinley – (5,190 meters or 20,310

feet), climb as high as you can on whatever number day you are

on, establish a camp and then go down AT LEAST 150 to 200

meters (492 to 656 feet) to sleep – you will sleep better and

exponentially reduce your chances of trying to sleep through a

miserable night. You will also feel much better in the morning.

In addition, while climbing, all experienced backpackers know

they should hike/climb for 45 minutes of every hour and take

a break for 15 minutes – giving the body a rest break helps with acclimatization. Whenever you take a break and feel

the slightest symptoms of AMS, HAPE or HACE, come down

immediately at least 150 meters (482 feet). As Mountaineering

Physicians who run a non-profit wilderness organization (www.

wildernessphysicians.org) for the past twenty years, we have

recovered many dead “macho men” off of a mountain or simply

had to leave them there as eternal popsicles to remind other

climbers of what not to do!! No organization, including ours, will

EVER risk the lives of their Rescue Physicians, Rescue Teamsor

Search and Rescue Dogs to drag a corpse off a mountain – this is

the brutal reality of High Altitude Mountaineering!!

Despite years of careful research the exact causes of HAPE

remain poorly understood. Fluid has been shown to fill up the

alveoli in the lungs preventing oxygen getting into the blood

and causing the vicious circle of events that can kill people with HAPE. As with many biological processes, many factors play

a role in this condition and there is good evidence to support

a number of theories about how this fluid accumulates in the

lungs.

Normally, oxygen gets into your blood and is supplied to the

body from your lungs. Each time you take a breath in, air rushes

into the tiny alveoli at the end of all the bronchioles in your

lungs. At the same time, blood from your heart is brought close

to these thin-walled alveoli so that oxygen can move into your

blood while waste products move out. Oxygen-rich blood then

returns to the heart and is distributed to the body. If, by accident,

a person inhaled a small object into their lungs, it would become

stuck in one of the airways branches. Little oxygen would get to

the downstream alveoli. To prevent this area of lung supplying

blood starved of oxygen back to the heart (and therefore the rest

of body), blood vessels in this area will constrict, self-protecting

the body.

At high altitudes however, this same process occurs and is a

cause of the disorder HAPE. The entire lung is starved of oxygen

and therefore the entire lung reacts in the same way – blood

vessels start constricting everywhere within the lung and not just

in small areas. The blood in these vessels is constricted and the

pressure goes up, the permeability of the vascular endothelium

increases and fluid is forced out of the blood and into the alveoli.

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are formed in your blood when

a patient is starved of oxygen. Some of these highly damaging

molecules are produced as follows: The reduction of molecular

oxygen (O2) produces Superoxide (•O2−); Dismutation of

Superoxide produces Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2); H2O2 in turn

may be partially reduced to a hydroxyl radical (•OH) or fully

reduced to water (H2O), which fills the alveoli. The hydroxyl

radical is so extremely reactive that it immediately removes

electrons from any molecule nearby, turning that molecule into

a free radical and so propagating a chain reaction.These highly

reactive molecules can directly damage the alveolar membranes

between the air and blood in the lungs, causing further fluid

leakage into the alveoli and worsening HAPE.

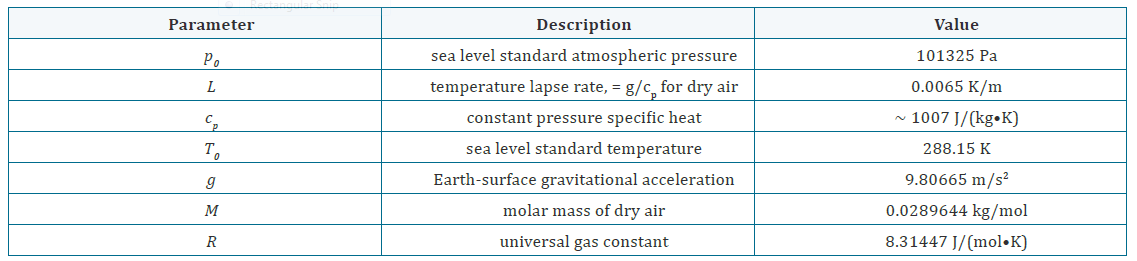

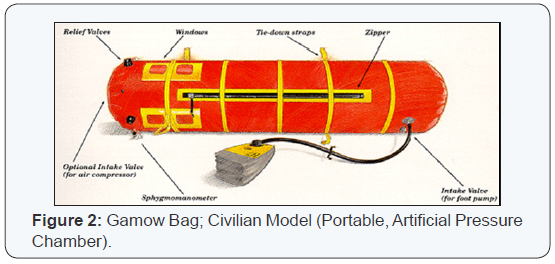

The most important treatment for HAPE is descent.

Providing extra oxygen and/or raising the air pressure around

a victim with a Gamow Bag (Figure 2) can partially reverse the

underlying process, lack of oxygen, but these measures are not a

permanent substitute for rapid descent down the mountain. The

patient is placed in a sleeping bag and then inside the Gamow

Bag. The foot pump is used to increase the internal pressure of

the bag and this in effect lowers the “altitude” that the patient

is experiencing. There is also a port that allows oxygen to

be connected and insufflated, helping increase the patient’s

pO2. Again, the patient still has to be rapidly moved down the

mountain as there is no way for a physician to physically touch the patient and treat him/her. The Gamow Bag is a temporary,

although extremely effective adjunct.

The primary author of this paper has personally seen the

Gamow Bag actually save the life of a patient on top of California’s

highest peak, Mount Whitney (14,505 ft. or 4,395 meters). This

author climbed Mt. Whitney with his Rottweiler in about 8 hours

and when he got to the top, there was a massive commotion going

on. A patient had literally dropped unconscious at the summit,

but unfortunately he was the group’s paramedic and was totally

unresponsive. The author took over and by the basic history he

could gather from the hysterical group, the patient had either

HAPE or HACE, although the author suspected HACE, due to the

rapid deterioration and unconsciousness. The author found that

they actually had a packaged, brand new Gamow Bag in their

medical supplies, but no one even knew what it was. We placed

the paramedic-victim in a sleeping bag, then into the Gamow

Bag; pressurized the Gamow Bagand hooked up the Rottweiler

by her harness to the bag. The dog dragged the patient all the way

down to a road that went about ⅓ of the way up the mountain,

for people that didn’t want to climb the mountain from the

base. (This was the problem, a relatively small climb on a high

mountain with absolutely no acclimatization). These people

had all their vehicles there but were from a different state, so we took one of the trucks with the patient, the author and the

Rottweiler in the back and we took the patient to the nearest

hospital, about a two hour drive at 100 mph (161 kph). In the

meantime, the author had opened the Gamow Bag, started an I.V.

TKO and eventually the patient made a full recovery. No drugs

were available as this was the paramedics’ personal medical kit

and paramedics in California are not allowed to possess or give

any drugs without a direct order from a physician. The Gamow

Bag saved his life for sure and is one of the best investments a

mountaineering group can make. Current 2016 pricing: $2,110;

€1,942; £1,465.

Some drugs can be helpful, but should only be used by

trained doctors, there for no dosing will be provided here as this

article can be read by anyone. Nifedipine is a drug that helps to

open up the blood vessels in the lungs. By doing so, it reduces

the high pressure in those vessels that is forcing fluid out into

the lungs. Following recent research, physicians may also give

the steroid, dexamethasone. Drug treatment should only ever be

used as a temporary measure; the best treatment is descent.

HAPE also causes breathlessness due the increased fluid

in the lungs. It is never normal to feel breathless when you are

resting - even on the summit of Everest. This should be taken

as a sign that the patient has HAPE and may die soon. HAPE

can also cause a fever and coughing up frothy, bloody sputum.

HAPE remains the major cause of death related to highaltitude

exposure with a high mortality in absence of adequate

emergency treatment.

Physiological and symptomatic changes often vary according

to the altitude involved. The Lake Louise Consensus Definition

for High Altitude Pulmonary Edema [4] has set widely-used

criteria for defining HAPE symptoms.

- The patient should have at least two symptoms [5]:

- Dyspnea at rest

- Cough

- Weakness or decreased exercise performance

- Chest Congestion

- The patient should have at least two signs [5]:

- Crackles or wheezing in at least one lung field

- Central Cyanosis

- Tachypnea

- d.Tachycardia

- Intermediate Altitudes (1,500 – 2,500 meters or 4,950 – 8,250 feet)

- Clinical symptoms are unlikely

- Blood oxygen levels remain >90%

- Clinical symptoms are common

- May develop after 2 to 3 days

- Blood oxygen levels may drop below 90% or lower during exercise

- Prior acclimatization will decrease the severity of the symptoms.

- Extreme Altitude (>5800 meters or 19140 feet)

- Blood oxygen levels are <90%, even at rest

- Progressive deterioration may occur despite acclimatization

If a travelling companion has symptoms of acute mountain

sickness and becomes confused or unsteady or develops an

extremely severe headache or vomiting, they may have the

life-threatening condition called High Altitude Cerebral Edema

(HACE).

There are many remedies touted as treatments or “cures”

for altitude sickness, but there is no evidence to support any of

them. The only chance the patient has is IMMEDIATE evacuation

to as low an altitude as possible. Put the patient in a Gamow Bag

if one is available.

HACE is high altitude cerebral edema and is a build-up

of fluid on the brain. HACE is extremely life-threatening and

requires urgent action.

HACE is the most severe form of acute mountain sickness

[6]. A severe headache, vomiting and lethargy will progress to

unsteadiness, confusion, drowsiness and ultimately a coma.

Drowsiness and loss of consciousness occur shortly before death.

HACE can kill in only a few hours, so the treating person must act

immediately. If you wait a “few hours” until it is light enough to

see, the patient will either die waiting to be evacuated or shortly

thereafter. A person with HACE will find it difficult to walk heelto-

toe in a straight line (ataxia) – this is a useful test to perform

on someone with severe symptoms of acute mountain sickness.

HACE should also be suspected if a companion starts to behave

irrationally or bizarrely. Protect the patient from hurting him

or herself by removing or hiding anything sharp or dangerous

objects (such as climbing axes) or weapons.

About 1% of people who ascend to over 3,000meters (9,900

ft.) get HACE. The lowest altitude at which a case of HACE has

been reported was 2,100meters (6,930 ft.). HACE can also occur

in people with HAPE and vice versa. Factors that increase the

risk of HACE are similar to those for acute mountain sickness and

HAPE. The faster the rate of ascent and the higher the altitude, the

more likely it is that HACE will develop. HACE is thought to occur

mainly in trekkers or climbers who have ignored symptoms of

acute mountain sickness and continued climbing higher rather

than staying at the same altitude or descending.

The cause of HACE, like HAPE, remains unknown. Several

factors may play a role including increased blood flow to the

brain. An increase in blood flow is a normal response to low

oxygen levels in the brain as the body needs to maintain a constant

supply of oxygen to the brain. However, if the blood vessels in the

brain are damaged, fluid may leak out of the vessels [7] and cause

HACE. The skull is an immobile encasement designed to protect

the brain, but any additional fluid will increase intracranial

pressure, contributing to HACE and in the extreme, causing an

Uncal Herniation (a subtype of transtentorial downward brain

herniation) and instant death.

As mentioned before, HAPE and HACE often occur together,

so as the treating physician, do not waste time trying to ascertain

which one the patient has, just get the patient evacuated to a

lower altitude as soon as possible.

Again, as with HAPE, rapid descent is the most effective

treatment of HACE and should not be delayed if HACE is suspected. A Gamow Bag (Portable Pressure Chamber - Figure

2), can be used as a temporary measure and, if available, oxygen

and a drug called dexamethasone should be given, but only by a

physician [8].

Altitude sickness occurs when an individual who is

accustomed to low altitudes rapidly climbs to a high altitude [8].

Altitude sickness is a potentially lethal complication of climbing

to altitudes above 8,000 feet (2,425 meters) [9-11]. Three

main syndromes of altitude illness may affect travelers: Acute

Mountain Sickness (AMS), High Altitude Pulmonary Edema

(HAPE) and High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE). The risk of

dying from altitude related illnesses is low, at least for tourists.

For trekkers to Nepal the death rate from all causes was 0.014%

and from altitude illness 0.0036%, soldiers posted to altitude

had an altitude related death rate of 0.16%.

Treatment of altitude related illness is to stop further

ascent and if symptoms are severe or getting worse, to descend

immediately! DO NOT DELAY!! Oxygen, drugs, Gamow Bags

and other treatments for altitude illness should be viewed as

adjuncts to aid descent, NOT AS PRIMARY TREATMENTS!

The Death Zone is the name used by mountain climbers for

high altitude where there is not enough oxygen for humans to

breathe. This is usually above 8,000 meters (26,400 feet). Most

of the 200+ climbers who have died on Mount Everest have died

in the death zone.

No human patients were used in the development and writeup

of this paper.

To know more about Open Access International

Journal of Pulmonary & Respiratory Sciences please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ijoprs/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment