Effectiveness of Mhealth to Increase Cervical Cancer Screening: Systematic Review of Interventions-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PULMONARY & RESPIRATORY SCIENCES

Abstract

Background: Estimated one

million-plus women worldwide are currently living with cervical cancer.

Many of them have not any access to health services for prevention,

curative treatment or palliative care. Cervical cancer is a consequence

of a long-term infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), and the

majority of cervical cancer cases (>80%) are currently found in low-

and middle-income countries. In fact, an increasing body of literature

indicates that HIV-positive women have an increased risk of developing

cervical cancer in comparison with their HIV-negative counterparts.

Cervical cancer is most notable in the lower-resource countries of

sub-Saharan Africa as the result of the highest incidence of

HIV-infected women.

Pilot mHealth projects have shown that, particularly

in developing countries, mobiles phones improve communication and

information-delivery and information-retrieval processes over vast

distances between healthcare service providers and patients. Mobiles

phones provide remote access to healthcare facilities, facilitate

trainings for, and consultations among health workers, and allow for

remote monitoring and surveillance to improve public health programs

awareness.

mHealth interventions can potentially influence

health-related behavior (and, in turn, health outcomes) via effecting

changes in mediators of behavior change such as knowledge, attitudes,

community peer norms, beliefs and self-efficacy. SMS can be customized

to fit the needs of specific individuals by delivering tailored messages

that are more likely to catch the individual’s attention and be

perceived as personally relevant and interesting.

This systematic review will investigate whether mHealth interventions could improve cancer screening uptake in risk women.

Objective: To assess the

effectiveness of different mHeath (SMS, calls, letters and emails

reminders) interventions to improving cervical cancer screening in risk

women.

Search methods: We searched for

studies in MEDLINE, Scorpus, PsychINFO, Cochrane Central Register of

Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, World Health Organization Global

Health Library regional index, Mobile Active http://

www.mobileactive.org, Web of Science and Grey literature. In addition,

hand-searching was performed for the original published version of this

review, but not for this update. Issues of the following journals will

be hand-searched: AIDS, AIDS Care, Health Education Journal, Health

Psychology and Journal of the American Medical Association

Selection criteria: We included the

following studies design: randomized control trials, quasi-experimental

studies and non-randomized control trials assessing different mHealth

interventions in improving cervical cancer screening outcomes.

Data collection and analysis: Two

reviewers independently (JT and LM) identified and critically appraised

all included studies. Study design, characteristics of study

populations, interventions, controls and study results were extracted by

two review authors. In addition, the risk of bias of included studies

was assessed independently by two reviewers. We interpreted the results

from meta-analysis. We reported the odds ratio with 95% confidence

intervals for the different outcomes.

Main results: We found 4731 studies

in different electronic databases, 3004 studies were included after

removing duplicated studies. Among them, 79 studies were fully assessed

and then, 51 were excluded and 28 studies were assessed for eligibility

criteria. 11 studies were excluded with reasons and 17 studies were

included in meta-analysis. The overall results revealed that call

reminders increased 44% of cervical cancer screening compared to the

standard care, with p-value of0.01. 8 studies were included in this

meta-analysis and the total number of participants was 29477. Call

reminders improved 89% of cervical cancer screening adherence, with

highly statistical results (Test for overall effect: Z = 5.23, P <

0.00001). 3 studies and 1340 participants were included. Lastly, letter

reminders improved 20 % of cervical cancer screening compared to the

standard care. 8 studies and 345835 participants were found in the

overall results. Therefore, this result was not statistically

significant (P=0.15).

The effect of call reminders on cervical cancer

screening and its adherence was high; therefore the impact of letter

reminders on cervical cancer was moderate.

Authors’ conclusion: This systematic

review supports the use of call reminders in improving cervical cancer

screening and adherence to testing. The main outcomes were graded as

high level of evidence. Then, call reminders could be suggested to be

encompassed in different national policy in screening cervical cancer in

risk populations. The lack of sufficient evidence on the subject limits

the reliability of the current cervical cancer screening guidelines for

high risk women is the leading cause of diagnosing cervical cancer in

the last stage. Further studies in this field will provide the sole for

preventing cervical cancer. However, this review could orientate public

health policy makers.

Background

Description of the condition

An estimated one million-plus woman worldwide is currently

living with cervical cancer [1]. Many of them have not any access

to health services for prevention, curative treatment or palliative

care [1]. Cervical cancer is a consequence of a long-term infection

with human papillomavirus (HPV), and the majority of cervical

cancer cases (>80%) are currently found in low- and middleincome

countries [1].

Nowadays, Cervical cancer constitutes a major health problem

worldwide [2]. Recent studies have demonstrated cervical cancer

is the leading cause of female cancer mortality and second most

common cancer in women worldwide [3] and It is responsible for

528,000 new cases of cancer and causes 270,000 deaths each year

(WHO 2012) [4]. Several demographic, economical and behavioral

risk factors have been studied in relation to cervical cancer [5].

Most of them may influence the risk of cancer through their

effects on the risk of HIV and HPV infection Ali-Risasi [5]. Different

studies have shown that HIV infection has been associated with an

increased risk of cervical cancer Kumakech [6]. Epidemiological

studies have clearly established human papillomavirus (HPV)

infection as the main cause of cervical cancer. In most studies,

HPV16 and HPV18 are the predominant genotypes: they cause

about 70 % of precancerous lesions and cervical cancer [7,5]. In

Sub- Saharan Africa however, other oncogenic genotypes have

been reported 5,8,9,10]. In fact, an increasing body of literature

indicates that HIV-positive women have an increased risk of

developing cervical cancer in comparison with their HIV-negative

counterparts [11,12]. Sub-Saharan has the highest incidence of

HIV-infected women, and then cervical cancer is most notable in

the lower-resource countries of sub-Saharan Africa [4]. In sub-

Saharan Africa, 34.8 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed

per 100 000 women annually, and 22.5 per 100 000 women die

from the disease [4]. Compared to North America where there are

6.6 new cases of cervical cancer diagnosed per 100 000 women

annually, and 2.5 per 100 000 women die, Sub-Saharan Africa

has 34.8 and 22.5 per 100 000 respectively [4].With increasing

attention to cervical cancer prevention in developing countries

[13], several pilot screening programs have been initiated

throughout sub-Saharan Africa Rosser [14]. The World Health

Organization (WHO) recommends a more aggressive cervical

cancer screening [15].

In fact, among all malignant tumours, cervical cancer is the

one that is most easily preventable by screening Arbyn M [16].

The detection of cytological abnormalities by microscopic

examination of “Pap smears”, and the subsequent treatment

of women with high-grade cytological abnormalities, avoids

development of cancer [16,17]. With increasing attention to

cervical cancer prevention in developing countries, several pilot

screening programs have been initiated throughout sub-Saharan

Africa [14]. Therefore, some challenges are associated with

screening, ranging from low levels of cervical cancer screening due

to poor access to organized screening, a lack of or low information

on cervical cancer screening, stigma, women’s perception of low

threat of disease and overburdened health care facilities which

lack equipment and are understaffed [18,19].

Description of the intervention

Mobile telecommunication technologies into the health

arena is also known as mobile health, mHealth or eHealth [20].

Mobile phone technology is increasingly viewed as a promising

communication channel that offers the potential to improve health

care delivery and promote behavior change among vulnerable

populations [20].

Pilot mHealth projects have shown that, particularly in

developing countries, mobile phones improve communication and

information-delivery and information-retrieval processes over

vast distances between healthcare service providers and patients

[21,22]. Mobiles provide remote access to healthcare facilities,

facilitate trainings for, and consultations among, health workers,

and allow for remote monitoring and surveillance to improve

public health programs. This phenomenon has the potential to

lead to an overall increase in the efficiency and effectiveness of

under-resourced health infrastructures, ultimately translating

into benefits for patients [22].

SMS-based interventions enable patients and providers to

‘‘interact’’ via two-way communication. To date, this feature has

been implemented in various ways. For example, most studies

have used systems to automate the message delivery process for

providers, ranging from fully automated clinical appointment

reminders [23] to staff developing and delivering the messages

themselves. SMS interventions also have enabled patients to

communicate with providers to confirm thier adherence to any

health interventions or outcomes [24,25]. Other studies have

mixed SMS, call, email and letter reminders to improve health

related outcomes. In fact, letter reminders could be used in

network inaccessible areas or cellphone deprived women.

The use of mHealth to improve health related outcomes is

receiving more attention in public health as emerging evidence

suggests reminder messages, call, email and letter can improve

several health outcomes.

How the intervention might work

Individual and cultural factors, such as stigma, isolation,

symptoms of illness, and psychological distress [26-28] may

contribute then to non-adherence of cervical cancer screening.

mHealth interventions can potentially influence healthrelated

behavior (and, in turn, health outcomes) via effecting

changes in mediators of behavior change such as knowledge,

attitudes, community peer norms, beliefs and self-efficacy [29].

SMS can be customized to fit the needs of specific individuals by delivering tailored messages that are more likely to catch the

individual’s attention and be perceived as personally relevant

and interesting [30]. Then, mHealth plays an active role in one’s

health and medical care leads to better healthcare quality, better

clinical health outcomes, and likely lower healthcare costs [31].

Interventions aimed at increasing patient involvement have

shown beneficial effects on satisfaction and functional status

[32,25], quality of life [33], perceived control over cervical cancer.

Why it is important to do this review

Studies have shown that well-organized cytological

screening at the population level, every three to five years,

and the incidence of cervical cancer can be reduced up to 80%

[34,16]. Furthermore, the vaccination against the most common

oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) types, HPV-16 and HPV-

18, could prevent development of up to 70% of cervical cancers

worldwide [35]. Therefore, this vaccine is quite inaccessible in

developing countries; by the way, the Pap smear reminds the

cornerstone of cervical cancer screening in developing countries.

Then, improving cervical screening through different behavioral

intervention is the only way that could decrease drastically the

morbidity and mortality of cervical cancer.

Eight studies exploring reasons women did not utilize cervical

cancer screening were included. Women in Sub-Saharan Africa

reported similar barriers despite cultural and language diversity

in the region [36]. Women reported fear of screening procedure

and negative outcome, low level of awareness of services,

embarrassment and possible violation of privacy, lack of spousal

support, societal stigmatization, cost of accessing services and

health service factors like proximity to facility, facility navigation,

waiting time and health care personnel attitude [36].

This systematic review will investigate whether mHealth

interventions could improve cancer screening uptake in risk

women.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of different mHeath (SMS, calls,

letters and emails reminders) interventions to improving cervical

cancer screening in risk women.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

- Randomized control trials

- Quasi-experimental studies

- Non randomized control trials

4.3. Types of participants

Women at risk of developing cervical cancer

Types of interventions

SMS reminders

- Call reminders

- E-mail reminders

- Letter reminders

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes- Pap smear uptake

- Adherence to test pap smea

Proportion of abnormal pap smear

Search methods for identification of studies

(Cellular phone) OR (telephone) OR (mobile phone) OR (text

messag*) OR (testing) OR (short messag*) OR (cell phones) OR

(SMS) OR (short message service) OR (text) OR (mobile health)

OR (telemedicine) OR (health) OR (health communication) OR

(health education) OR (behavior) OR (ehealth)

(Uterine Cervical Neoplasm) OR (Cervical Neoplasms)

OR (Cervical Neoplasm) OR (Cervix Neoplasms) OR (Cervix

Neoplasm) OR (Cancer of the Uterine Cervix) OR (Cancer of the

Cervix) OR (Cervical Cancer) OR (Uterine Cervical Cancer) OR

(Cancer of Cervix) OR (Cervix Cancer)

(Test, Papanicolaou) OR (Pap Test) OR (Test, Pap) OR (Pap

Smear) OR (Smear, Pap) OR (Papanicolaou Smear)

(Randomized controlled trial) OR (controlled clinical trial)

OR (randomized controlled trials) OR (random allocation) OR

(double-blind method) OR (single-blind method) OR (clinical

trial) OR (trial) OR (clinical trials) OR (clinical trial) OR (singl*

OR doubl*) OR (trebl* OR tripl*) AND (mask* OR blind*) OR

(placebos) OR (placebo*) OR (random*).

Electronic searches

We searched for studies in:

MEDLINE

- Scorpus

- PsychINFO

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

- CINAHL

- World Health Organization Global Health Library regional index

- Mobile Active http:// www.mobileactive.org

- Web of Science

- Grey literature

Hand-searching was performed for the original published

version of this review, but not for this update. Issues of the

following journals was hand-searched: AIDS, AIDS Care, Health

Education Journal, Health Psychology and Journal of the American

Medical Association.

Data Collection and Analysis

Selection of studies

Inclusion criteria was applied to all titles and, where available,

abstracts identified from the literature search by two review

authors. Potentially relevant references was then retrieve for

further screening by one review author and check by a second.

Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with recourse

to a third review author when necessary.

Data extraction and management

The following data were extracted:

- Author and year of publication

- Country, town, Setting

- study design

- Total number of intervention groups

- Unit of data analysis

- Sample size calculation

- Duration of follow-up

- total number enrolled

- Eligible participants

- Age

- Ethnicity

- Intervention details: type of intervention, description of intervention, frequency and duration of intervention

- comparator group(s)

- Outcomes measures

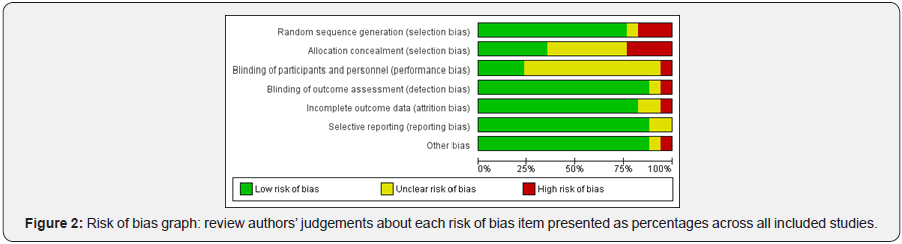

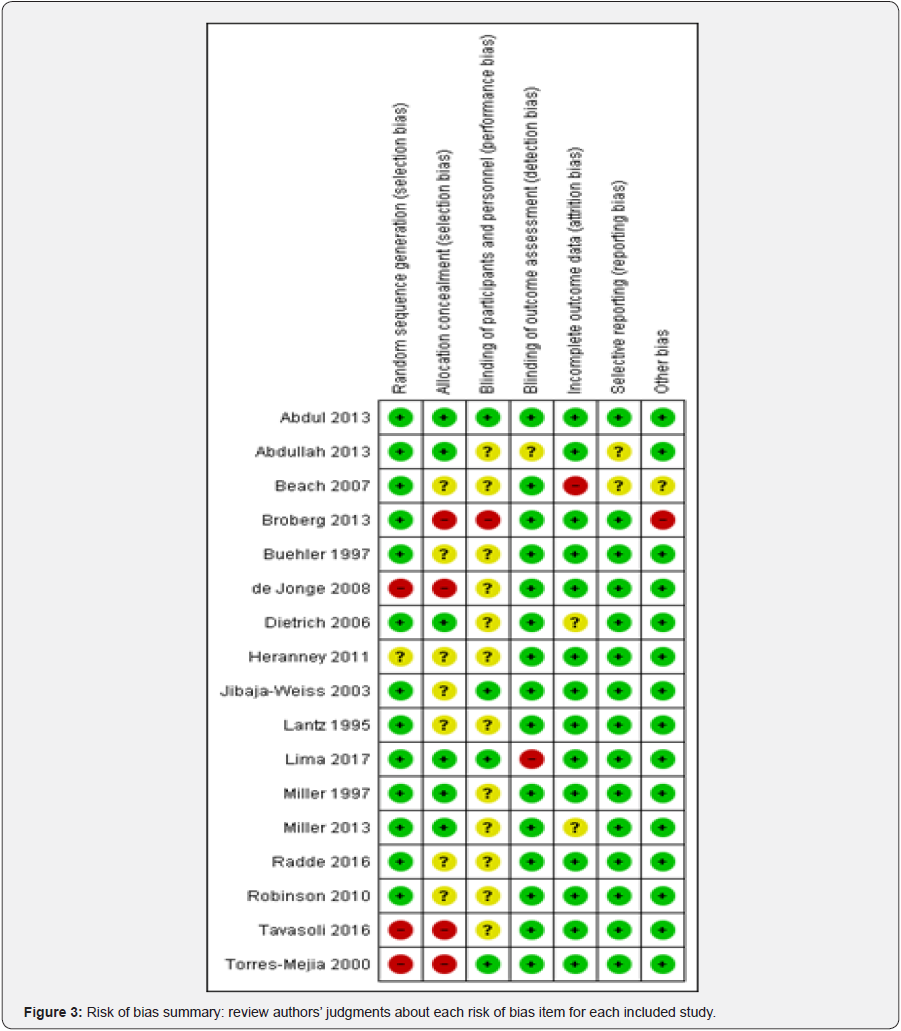

Risk of bias assessed in included studies using the Cochrane

Collaboration’s Risk of Bias tool. The tool includes the following

domains: random sequence generation; allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel; blinding of outcome

assessment; incomplete outcome data; selective reporting; and

other sources of bias. Any disagreement will be resolved by

consensus, by consulting a third author.

Measures of treatment effect

We used only dichotomous outcomes we used the odds ratio

and its 95% CI was calculated.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was individuals. After adjustment for

possible confounding, data derived from cluster-randomized

controlled trials produced same results. We included clusterrandomized

trials in the meta-analysis along with individuallyrandomized

trials. We adjusted for design effect using an

‘approximation method’.

Dealing with missing data

We did not experience any missing data in this systematic review

Heterogeneity between trials was assessed by visual

inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage of I2

between trials which could be ascribed to sampling variation, by

a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity

and, if possible, by sub-group analyses. If we find substantial

heterogeneity, the possible reasons for this was investigated and

reported.

Funnel plots corresponding to meta-analysis of the primary

outcome was examined if we have 10 or more studies. We then

assessed the potential for small study effects. If there is evidence

of small-study effects, publication bias was considered as only

one of a number of possible explanations. If these plots suggested

that treatment effects may not be sampled from a symmetric

distribution, as assumed by the random effects model, sensitivity

analyses was carried out using fixed effects models.

Data synthesis was based on the heterogeneity of the studies.

When heterogeneity was not too large, we performed a metaanalysis.

In the presence of homogeneity, we used a fixed-effect

model for the meta-analysis. In the case of moderate or high

heterogeneity, we used a random-effects model to produce the

overall results.

Results

Results of the search

Seventeen studies were included in this systematic review

(see annex tables: Characteristics of included studies). Twelve

RCTs [2,37-47], two cluster randomized control trials [48,49], two

quasi-randomized control trial [50,51] and one non randomized

control trial [52].

Excluded studies

Ten studies were excluded from the review among which [53-

62] (see annex tables: Characteristics of excluded studies)

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation (selection bias)

Allocation concealment was minimized in Abdul [37];

Abdullah F [48]; Dietrich [40]; Lima [51]; Miller [44]; Miller [2];

Radde [45]. In Beach [49]; Buehler [39]; Heranney [41]; Jibaja-

Weiss [42]; Lantz [43]; Robinson [46], selection bias was unclear,

therefore high in Broberg [38]; de Jonge [50]; Tavasoli [52];

Torres-Mejia [47].

Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

Bias assessment stool revealed that performance bias was

reduced in Abdul [37]; Abdullah [48]; Lima [51]; Jibaja-Weiss [42];

Torres-Mejia [47]. unclear Beach [49]; Buehler [39]; de Jonge [50];

Dietrich [40]; Heranney [41]; Lantz [43]; Miller [44]; Miller [2];

Radde [45]; Robinson [46]; Tavasoli [52] and high Broberg [38].

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

We found that incomplete outcome data(attrition bias) Abdul

[37]; Abdullah [48]; Broberg [38]; Buehler [39]; de Jonge [50];

Heranney [41]; Jibaja-Weiss [42]; Lantz [43]; Lima [51]; Miller

[44]; Radde [45]; Robinson [46]; Tavasoli [52]; Torres-Mejia [47]

were low risk of bias, Dietrich [40]; Miller [2] were unclear and

Beach [49] was high.

Selective reporting (reporting bias)

Critical appraisal revealed that Abdul [37]; Broberg [38];

Buehler [39]; de Jonge [50]; Dietrich [40]; Heranney [41]; Jibaja-

Weiss [42]; Lima [51]; Radde [45]; Tavasoli [52] were low risk of

bias. Therefore Lantz [43]; Miller [44]; Miller [2]; Robinson [46];

Torres-Mejia [47] were unclear and Abdullah [48]; Beach [49]

were high risk of bias

Other potential sources of bias

We judged as low risk of bias Abdul [37]; Abdullah [48];

Buehler [39]; de Jonge [50]; Dietrich [40]; Jibaja-Weiss [42]; Lantz

[43]; Lima [51]; Miller [44]; Miller [2]; Radde [45]; Robinson [46];

Tavasoli [52]; Torres-Mejia [47] as unclear Beach [49]and Broberg

[38]; Heranney [41] were judged as high risk of bias (Figure 2 & 3).

Summary of Main Results

Call reminders and cervical cancer screening

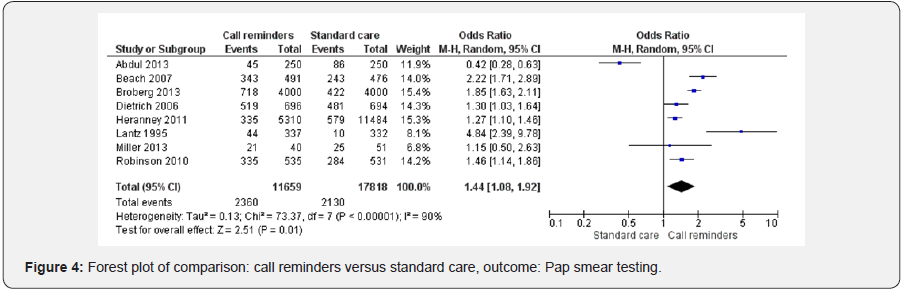

Height studies [2,37,38,40,41,43,46,49] were included in

the forest plot analyzing the effect of call reminders on cervical

cancer screening in risk women. Call reminders were statistically

significant in increasing cervical cancer screening compared to

the standard care (OR 1.44 95% CI 1.08, 1.92, 29477 participants,

8 studies, Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; Chi² = 73.37, df = 7 (P <

0.00001); I² = 90%, random effects). Test for overall effect: Z =

2.51 (P = 0.01) (Figure 4).

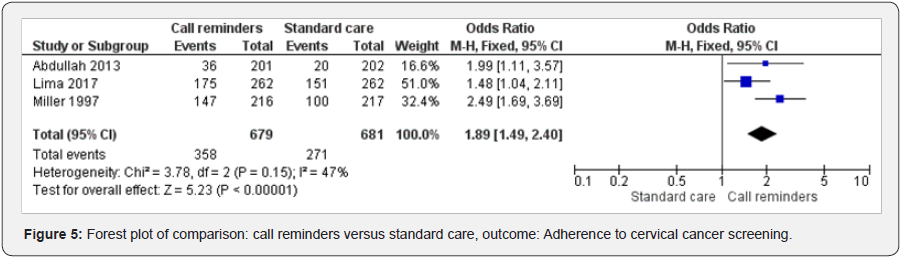

Call reminders and adherence to cervical cancer screening

Three studies [48,51,44] were included in examining the

effect of call reminders on cervical cancer screening adherence.

Call reminders versus standard care has shown statistically

significant results (OR 1.89 95% CI 1.49, 2.40, 1360 participants,

3 studies). Heterogeneity: Chi² = 3.78, df = 2 (P = 0.15); I² = 47%,

fixed effects). Test for overall effect: Z = 5.23 (P < 0.00001) (Figure 5).

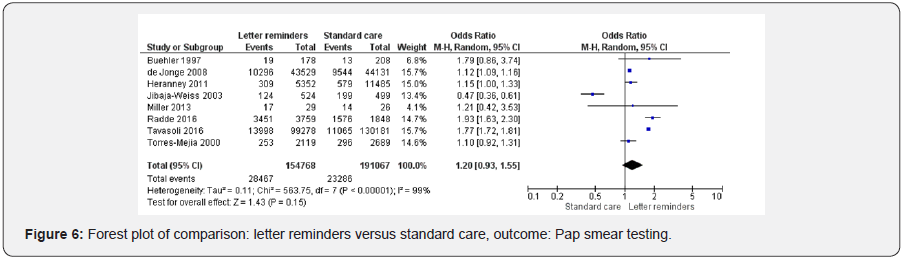

Letter reminders and cervical cancer screening

Height studies were included in letters reminders versus

standard care [39,41,42,2,45,52,47,50]. Letter reminders did not

improve cervical cancer screening (OR 1.20 95% CI 0.93, 1.55,

345835 participants, 8 studies, Heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.11; Chi²

= 563.75, df = 7 (P < 0.00001); I² = 99%, random effects). Test for

overall effect: Z = 1.43 (P = 0.15) (Figure 6).

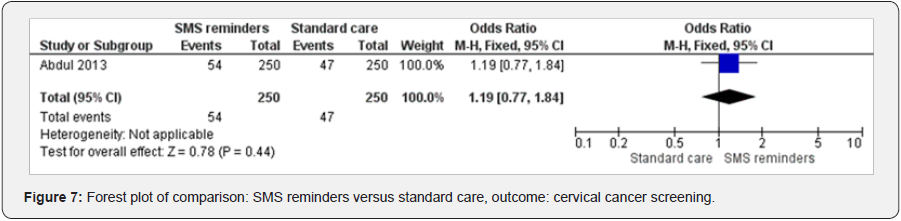

SMS reminders and cervical cancer screening

One study analyzed the effect of SMS reminders on cervical

cancer [37]. SMS reminders increased cervical cancer screening

(OR 1.19 95%CI 0.77 to 1.84, 500 participants, 1 study, test for

heterogeneity not applicable, fixed effects) (Figure 7).

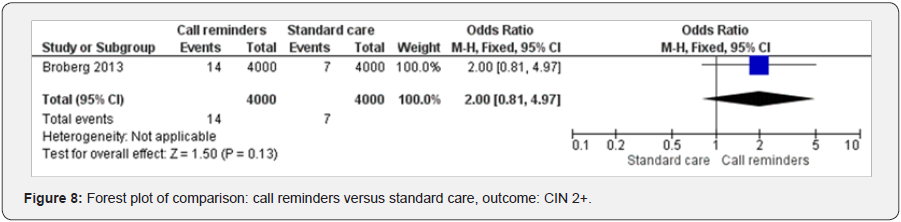

Call reminders and CN 2+

One study examined the effect of call reminders on diagnosing

CN 2+ [38]. The result has shown the call reminders improved CN

2+ diagnostic (OR 2.00 95% CI 0.81 to 4.97, 8000 participants, 1

study, test for heterogeneity not applicable, fixed effects) (Figure 8).

Discussion

The overall completeness and applicability of evidence could

be judged high when we considered the impact of call reminders

on cervical cancer screening and adherence to screening. This

illustrated the strength of this review. Then, this study could

influence public health policy in screening cervical cancer in risk

population. This evidence is strengthened by a recent review

that has shown automated telephone communication systems

interventions can modify patients’ health behaviors, improve

clinical outcomes and increase healthcare uptake with positive

effects in multiple health areas among which immunization,

screening, appointment attendance, and adherence to medications

or tests [63].

Letter reminders have shown to improve cervical cancer

screening outcomes; therefore the results were not statistically

significant compared to recent studies conducted in this field

[45,52]. The quality of evidence was moderate when analyzing

the effect of letter reminders on cervical cancer screening

in risk population. Letter reminders could still constitute an

option in improving cervical cancer screening. However, these

strategies would be challenging to implement in the context of a

jurisdictionally centralized screening program [52].

We found only one RCT that investigated the effect of SMS

on cervical cancer screening. The result was not significant. In

addition, the quality of evidence was moderate. Further studies

should be conducted in this field even if several reviews have

shown positive effect of short messaging on health outcomes.

Only one RCT was found in analyzing the impact of mHealth on the

diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2. The quality

of evidence was moderate; the overall result was not significant.

Therefore, further studies are needful in this field.

Telephone interventions is a resource associated with the

nursing practice, which can produce significant changes in the

health outcomes, highlighting the importance of technical and

clinical knowledge for the interventions by the professional [51].

Furthermore, the use of technology for healthcare development

requires trained professionals to promote the convergence

between human development and technological knowledge,

aiming at the desired goals [51].

The lack of high-quality evidence on the prevention of cervical

cancer for high risk women, which is important for implementing

efficient screening and treatment strategies, results then in the

absence of a clearly defined health program in low and middle

income countries [13]. This is responsible for the low screening

uptake and high mortality rates [13].

As said above, several knowledge gaps might inhibit women

from undergoing cervical cancer screening. This review could

be useful in overcoming certain gaps, and then cervical cancer

screening could be ameliorated.

Authors’ conclusion

Nowadays, the risk of developing cervical precancerous

and cancerous lesions is high; therefore close monitoring and

specific schedule for follow constitute a big challenge. This review

supports the use of call reminders in improving cervical cancer

screening and adherence to testing. The level of evidence is high.Then, call reminders could be suggested to be incorporated

in different national policy in screening cervical cancer in risk

populations. The lack of sufficient evidence on the subject limits

the reliability of the current cervical cancer screening guidelines

for high risk women is the leading cause of diagnosing cervical

cancer in the last stage. Further studies in this field will provide

more solid foundations for preventing cervical cancer. However,

this review could orientate public health policy makers.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for all the review team in their different contributions.

To know more about Open Access International

Journal of Pulmonary & Respiratory Sciences please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ijoprs/index.php

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

To know more about juniper publishers: https://juniperpublishers.business.site/

Comments

Post a Comment