Diagnostic Criteria for the Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO) Still Room for Improvement-Juniper publishers

JUNIPER PUBLISHERS-OPEN

ACCESS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PULMONARY & RESPIRATORY SCIENCES

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a

heterogeneous disease in which the clinical presentation and prognosis

vary according to the phenotype [1]. In the last years, one of the

phenotypes of COPD, that is recognized as the Asthma-COPD Overlap (ACO)

has received increasing attention.

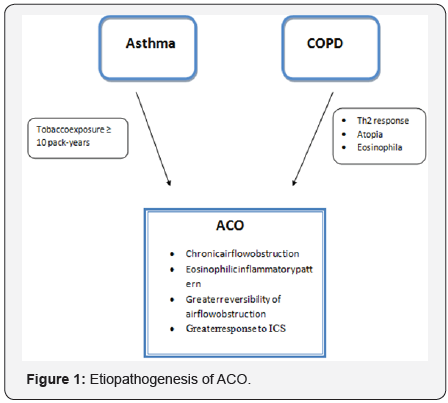

In contrast with the remaining COPD phenotypes,

patients with ACO present an elevated reversibility of airflow

obstruction as well as a greater degree of eosinophilic bronchial

inflammation, thereby demonstrating greater response to inhaled

corticosteroid (ICS) treatment [2-4]. These characteristics are

suggestive of asthma and can be explained by a history of asthma during

youth being an independent risk factor for the development of COPD in

smokers [5] (Figure 1).

From a clinical point of view, patients with ACO

present more symptoms, have a worse quality of life and a higher risk of

exacerbations than the remaining patients with COPD, but they have a

better survival. In the CHAIN study including125 COPD patients labeled

as having ACO and who fulfilled specific characteristics associated with

asthma according to some diagnostic criteria [major criteria:

bronchodilator test (BDR)>400ml and 15%or a history of asthma; minor

criteria: eosinophilia >5%, IgE> 100IU/ml or two BDR>200ml and

12 %] were found to have a greater one year survival compared to the

remaining patients with COPD without ACO [6].

Likewise, the cohort study by Hokkaido followed 268

patients labeled as having ACO who did not have a previous diagnosis of

asthma but fulfilled the characteristics of asthma (reversibility of

airflow obstruction ≥12 % and 200 ml, eosinophilia ≥300 eosinophils/μl

and/or atopy (specific IgE positive for at least one inhaled antigen),

and it was observed that despite these patients presenting a worse score

in the St. George quality of life questionnaire, they had a lower

mortality at 10 years compared to non ACOS patients probably because of

greater response to anti inflammatory treatment with ICS [7].

Globally, the prevalence of ACOS reported varies

greatly due to the different diagnostic criteria used. Different

epidemiological studies in which ACOS is defined as patients with COPD

diagnosed with asthma before the age of 40 described prevalences of 13%

and 17% [6,8]. Using the same definition, a multicenter,

cross-sectional, observational study carried out in Spain including 3125

patients with COPD in primary care and specialized centers reported a

prevalence of ACO of 15.9% [9]. The prevalence of ACO was determined to

be between 1.6 and 4.5% in the general adult population and between 15%

and 25 % in the adult population with COPD.

In the last years attempts have been made to define

the diagnostic criteria of this phenotype, but no definitive consensus

has been achieved. In Spain, a diagnostic consensus by the Spanish COPD

Guidelines (GesEPOC) was initially proposed, including very restrictive

criteria in which 2 major criteria or 1 major and 2 minor criteria had

be fulfilled for a patient to be defined as having ACO. The major

criteria included a very positiveBDR≥400ml and 15% compared to baseline,

eosinophilia in sputum and a personal history of asthma (prior to 40

years of

age), and the minor criteria were an elevated total IgE, a history

of atopy and a positive BDR ≥200ml and 12% on at least two

occasions [10]. Thereafter, an agreement between the Global

Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and the Global initiative for Chronic

Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) defined the ACO phenotype as

persistent airflow limitation with characteristics of both asthma

and COPD but did not clearly specify how many criteria should

be met to establish a diagnosis of ACO [11].

Later in 2016, a consensus was made among specialists in

North America, Europe and Asia, proposing 3 major criteria

(persistent airflow limitation <0.70 in patients over 40 years

of age, exposure to smoking of at least 10 packs-year or the

equivalent in biomass smoke exposure, a documented history

of asthma before age 40 or BDR>400ml in FEV1) and 3 minor

criteria (documented history of atopy or allergic rhinitis,

BDR≥200ml and 12%on at least 2 occasions, peripheral

eosinopilia ≥300eosinophils/μL). For a diagnosis of ACO, 3

major criteria and at least one of the minor criteria proposed

had to be met [12].

More recently, the new consensus between GesEPOC and

the Spanish Guidelines for the Management of Asthma (GEMA)

defined overlapping of asthma and COPD (ACO) as the presence

of chronic persistent airflow limitation, in a smoker or former

smoker [tobacco exposure≥10 pack-years] with a concomitant

diagnosis of asthma or with characteristics of asthma such as

very positive BDR (≥15% and ≥400ml) and/or blood eosinophilia

(≥300 eosinpophils/μL). Thus, the ACO phenotype includes not

only smoker asthma patients who develop persistent airflow

obstruction but also COPD with characteristics of asthma. To

fulfill this definition, airflow limitation must be persistent over

time, current or past smoking should be the main risk factor,

and the patient must present clinical, biological or functional

characteristics of asthma [13].

The diagnosis is sequential; the presence of chronic airflow

obstruction must first be confirmed with a post bronchodilator

FEV1/FVC ratio<0.70 in patients over 35 years of age who are

active or former smokers of at least 10 pack-years. In cases of

doubtful diagnosis, the patients should undergo spirometry

evaluation after at least 6 months of treatment with an ICS

and a long-acting β2 agonist (LABA). In case of reversibility of

airflow obstruction the diagnosis is asthma. After confirming the

persistence of chronic airflow obstruction, the current diagnosis

of asthma should be confirmed by a family or personal history

or asthma and/or atopy with respiratory symptoms (wheezing,

cough, chest oppression) or upper airway inflammation or

daily variability of PEF≥20% or exhaled nitric oxide fraction

(FENO≥50ppb). If the diagnosis of asthma cannot be established,

the diagnosis of ACO is confirmed if a patient with COPD presents

features of asthma: a very positive PBD (≥15% and ≥400ml) and/or the presence of eosinophilia in blood (≥300 eosinophils/

μL) [13].

Eosinophilia has shown to be a good biomarker to identify

COPD patients showing better response to ICS treatment who

fulfill the ACO criteria. However, the cut-off value is controversial.

In one study comparing stable COPD patients without ACO

with another stable COPD group with ACO, the patients with

ACO presented blood eosinophil concentrations double

those observed in the COPD group without ACO [14]. Studies

comparing eosinophilc inflammation in blood and sputum have

suggested that a cut-off value of ≥300eosinophils/μLin blood

is a good predictor of eosinophilia in sputum [15]. Different

consensuses recommend this cut-off of ≥300 eosinophils/μL in

peripheral blood [12,13].

With regard to the treatment of patients fulfilling ACO

criteria, the objectives are to prevent exacerbations as well as

maintain acceptable control of the symptoms and reduce the

grade of bronchial obstruction. The importance of diagnosing

ACO is to identify patients with COPD who require treatment

with ICS plus LABA from early phases of the disease.

Thus, the new GesEPOC-GEMA consensus establishes a

combination of LABA/ICS as the initial treatment. However, a

combination of choice cannot be recommended since no study

has compared different combinations [13]. Therefore, the

elevated doses of ICS currently recommended for the treatment

of COPD are associated with a greater incidence of adverse

effects, and a dose-response relationship with clinical efficacy

has not been demonstrated. Thus, intermediate doses of ICS are

recommended for the maintenance of these patients [16].

In more severe cases a long-acting anti cholinergic (LAMA)

may be added, constituting triple therapy (LABA/ICS/LAMA).

Although in the future some of these patients, particularly

the most severe not controlled with triple therapy, may be

candidates to treatment with new biological drugs, there are no

specific clinical trials on patients with ACO with this particular

phenotype.

Likewise, smoking cessation should be insisted upon as

should respiratory rehabilitation and the use of nasal anti

inflammatories and oxygen therapy in indicated cases [13].

To know more about Open Access International

Journal of Pulmonary & Respiratory Sciences please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ijoprs/index.php

To know more about Open access Journals

Publishers please click on : Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment